The cold was crisp and sharp like flint. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 1)

For a moment Fielding thought of Hecht pasturing in that thick body: it was a scene redolent of Lautrec. Yes, that was it! (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 1)

It was from us they learnt the secret of life: that we grow old without growing wise. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 1)

I used to think it was clever to confuse comedy with tragedy. Now I wish I could distinguish them. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 1)

Being alone was like being tired, but unable to sleep. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 1)

Nonconformity is the most conservative of habits. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 2)

‘The value of intelligence depends on its breeding.’ That was John Landsbury’s favourite dictum. Until you know the pedigree of the information you cannot evaluate a report. Yes, that was what he used to say: ‘We are not democratic. We close the door on intelligence without parentage.’ (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 2)

The only time they notice you is when you’re not there. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 3)

Smiley quickly noticed that he had one quality rare among small men: the quality of openness. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 3)

[…] but Fielding seemed so dazzled by the footlights that he was indifferent to the audience behind them. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 5)

The whiteness of the new snow lit the very sky itself; the whole Abbey was so sharply visible against it that even the mutilated images of saints were clear in every sad detail of their defacement, wretched figures, their purpose lost, with no eyes to see the changing world. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 6)

Built in an age when cactus was the most fashionable of plants and bamboo its indispensable companion, the lounge was conceived as the architectural image of a jungle clearing. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 7)

That’s where your village idiots come from. They call it the Devil’s Mark, I call it incest. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 7)

Somehow mundy managed to imply that the Black Death was a fairly recent disaster in those parts, if not actually within living memory. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 8)

[…]; once in the war he had been described by his superiors as possessing the cunning of Satan and the conscience of a virgin, which seemed to him not wholly unjust. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 9)

Smiley himself was one of those solitaries who seem to have come into the world fully educated at age eighteen. Obscurity was his nature, as wll as his profession. The byways of espionage are not populatedby the brash and colourful adventurers of fiction. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 7)

He said this as if ‘good’ were an absolute quality with which he was familiar. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 9)

Her very ugliness, her size and voice, coupled with the sophisticated malice of her conversation, gave her the dangerous quality of command. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 10)

It had been one of Smiley’s cardinal principles in research, whether among the incunabula of an obscure poet or the laboriously gathered fragments of intelligence, not to proceed beyond the evidence. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 11)

Rigby was right, it was impossible to know. You had to be ill, you had to be sick to understand, you had to be there in the sanatorium, not for weeks, but for years, had to be one in the line of white beds, to know the smell of their food and the greed in their eyes. You had to hear it abd see it, to be part of it, to know their rules and recognize their transgressions. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 11)

‘You don’t want anything brilliant,’ said Harriman. ‘You want a good, steady type. I’d take a bitch if I were you.’ (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 12)

[…] pondering on the strange byways of the military mind. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 12)

The business of assisting refugees has been suitably relegated to the south of the river, to one of those untended squares in Kennington which are part of London’s architectural schizophrenia. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 14)

[…] the rare gift of speaking to children as if they were human beings. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 14)

[…] the rare gift of contempt for what is urgent. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 14)

‘Black tie?’ asked Fielding, his pen poised, and some imp made Smiley reply:

‘I usually do, but it doesn’t matter.’ There was a moment’s silence. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 16)

‘Damned odd business. Experiments never pay, do they? You can’t experiment with tradition.’

‘No. No, indeed.’

‘That’s the trouble today. like Africa. Nobody seems to understand you can’t build society overnight. It takes centuries to make a gentleman.’ (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 17)

“You’ll kill me in the long nights!” She’d scream it out—it was the words that got her, the long nights, she liked the sound of them the way an actor does, and she’d build a whole story round them. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 19)

So many of us wait patiently for our audience to die. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 20)

‘That is the peace I mean. Not to exist in anyone’s mind, but my own; to be a secular monk, safe and forgotten.’ (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 20)

[…] ‘we just don’t know what people are like, we can never tell; there isn’t any truth about human beings, no formula that meets each one of us. […]‘ (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 20)

He had to reassure himself, you see, like a child being hateful to its parents. (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 20)

‘[…] The world sees them as showmen, fantasists, liars, as sensualists perhaps, not for what they are: the living dead.’ (Le Carré 1962: chpt. 20)

cold war cyberpunk

In my ↵post on John le Carré I somehow tried to vindicate my erupted interest in cold war spy fiction and my subsequent digesting of according novels and movies. Now ↑Bryan Alexander sent me excerpts from a ↑recent interview with ↑William Gibson, which force more mosaic tiles to fall in place:

INTERVIEWER: Was [Philip K.] Dick important to you?

GIBSON: I was never much of a Dick fan. He wrote an awful lot of novels, and I don’t think his output was very even. I loved The Man in the High Castle, which was the first really beautifully realized alternate history I read, but by the time I was thinking about writing myself, he’d started publishing novels that were ostensibly autobiographical, and which, it seems to me, he probably didn’t think were fiction.

[Thomas] Pynchon worked much better for me than Dick for epic paranoia, and he hasn’t yet written a book in which he represents himself as being in direct contact with God. I was never much of a Raymond Chandler fan, either.

INTERVIEWER: Why not?

GIBSON: When science fiction finally got literary naturalism, it got it via the noir detective novel, which is an often decadent offspring of nineteenth-century naturalism. Noir is one of the places that the investigative, analytic, literary impulse went in America. The Goncourt brothers set out to investigate sex and money and power, and many years later, in America, you wind up with Chandler doing something very similar, though highly stylized and with a very different agenda. I always had a feeling that Chandler’s puritanism got in the way, and I was never quite as taken with the language as true Chandler fans seem to be. I distrusted Marlow as a narrator. He wasn’t someone I wanted to meet, and I didn’t find him sympathetic—in large part because Chandler, whom I didn’t trust either, evidently did find him sympathetic.

But I trusted Dashiell Hammett. It felt to me that Hammett was Chandler’s ancestor, even though they were really contemporaries. Chandler civilized it, but Hammett invented it. With Hammett I felt that the author was open to the world in a way Chandler never seems to me to be.

But I don’t think that writers are very reliable witnesses when it comes to influences, because if one of your sources seems woefully unhip you are not going to cite it. When I was just starting out people would say, Well, who are your influences? And I would say, William Burroughs, J. G. Ballard, Thomas Pynchon. Those are true, to some extent, but I would never have said Len Deighton, and I suspect I actually learned more for my basic craft reading Deighton’s early spy novels than I did from Burroughs or Ballard or Pynchon.

I don’t know if it was Deighton or John le Carré who, when someone asked them about Ian Fleming, said, I love him, I have been living on his reverse market for years. I was really interested in that idea. Here’s Fleming, with this classist, late–British Empire pulp fantasy about a guy who wears fancy clothes and beats the shit out of bad guys who generally aren’t white, while driving expensive, fast cars, and he’s a spy, supposedly, and this is selling like hotcakes. Deighton and Le Carré come along and completely reverse it, in their different ways, and get a really powerful charge out of not offering James Bond. You’ve got Harry Palmer and George Smiley, neither of whom are James Bond, and people are willing to pay good money for them not to be James Bond.

cybernetic revolutionaries

In ↑Cybernetic Revolutionaries, Eden Medina tells the history of two intersecting utopian visions, one political and one technological. The first was Chile’s experiment with peaceful socialist change under Salvador Allende; the second was the simultaneous attempt to build a computer system that would manage Chile’s economy. Neither vision was fully realized—Allende’s government ended with a violent military coup; the system, known as Project Cybersyn, was never completely implemented—but they hold lessons for today about the relationship between technology and politics.

Drawing on extensive archival material and interviews, Medina examines the cybernetic system envisioned by the Chilean government—which was to feature holistic system design, decentralized management, human-computer interaction, a national telex network, near real-time control of the growing industrial sector, and modeling the behavior of dynamic systems. She also describes, and documents with photographs, the network’s Star Trek-like operations room, which featured swivel chairs with armrest control panels, a wall of screens displaying data, and flashing red lights to indicate economic emergencies.

Studying project Cybersyn today helps us understand not only the technological ambitions of a government in the midst of political change but also the limitations of the Chilean revolution. This history further shows how human attempts to combine the political and the technological with the goal of creating a more just society can open new technological, intellectual, and political possibilities. Technologies, Medina writes, are historical texts; when we read them we are reading history.

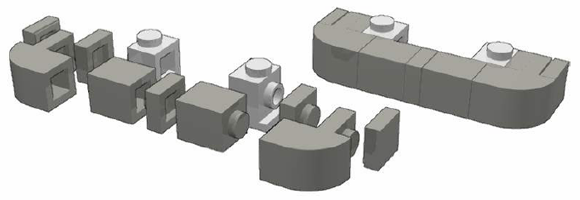

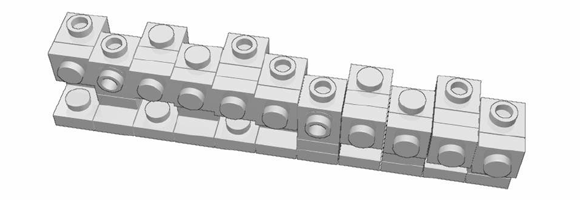

advanced building techniques

A common trait of technoludic online scenes and communities are the efforts undertaken to document, preserve and redistribute specific knowledge. The afols [adult fans of lego] have developed many building techniques beyond those found in official instructions. Back in 2007 Didier Enjary collected a lot of those in his ‘↓The Unofficial LEGO Advanced Building Techniques Guide‘ [.pdf | 1.7 MB]. Didier’s guide explains the geometry of LEGO bricks from scratch, then proceeds to particular techniques. All in all his guide is a testament to the afols’ intellectual and practical appropriation of the LEGO building system.

atlantis

Quite vividly do I remember when I sat in my parents’ living room on 12 April 1981, watching the launch of ‘Columbia’ on television. The ↑first flight of a ↑Space Shuttle into orbit. During the years when men walked the moon I was too young, and hence have no recollection of that at all. For me the Space Shuttle program was, like the Cold War, something that defined the world of my childhood. The Space Shuttles transposed what I read in comic books and science fiction stories into empirical, everyday reality. In July this year the era came to an end with the ↑last flight of Space Shuttle ‘Atlantis.’ Once I read somewhere that the Space Shuttle orbiters are the most complex machines mankind has built to date. Since 19 December 2011 a ↑set of wonderful photographies is online at collectSPACE, in a way giving a sense of this complexity.

Space shuttle Atlantis, which only five months ago flew the final mission of NASA’s 30-year shuttle program, is now being prepared for its public display at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Florida. Its insides being pulled out to ensure it is safe for exhibit, as well as significantly lighten it for its planned steep-angled display, Atlantis is scheduled to be powered down this week for the final time.

collectSPACE had the rare opportunity recently to tour Atlantis to photograph its preparation and capture its glass cockpit powered and lit for one of its last times.

seterra

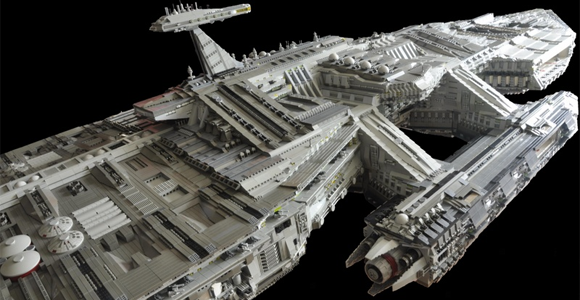

No, this is nothing out of a science fiction movie, but details of ‘↑Seterra,’ a moc [my on creation], more precisley a ↑SHIP [seriously huge investment in parts], by afol [adult fan of lego] ↑Thomas Haas. The huge construction (not a rendition of something seen on the silver screen, inspired though, but Thomas’ own design) is 3.8 m long, approximately 1.4 m wide and 0.6 m high. He has no idea how much parts he used during the three years of building time, but estimates its weight at about 60 to 80 kg. Sadly ‘Seterra’ exists no more—Thomas had to disassemble it. Over ↑at mocpages there is the full story and many, many more pictures.

whose arm?

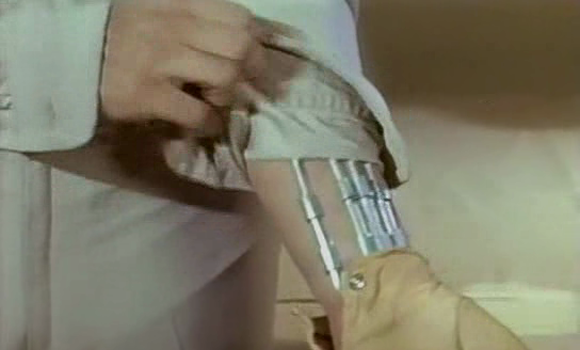

zeph’s pop culture quiz #8

Whose arm is that? The name of the actor will ring a big bell within the science fiction enthusiast—the story of this (today hardly known) movie a whole orchestra.

Just leave a comment with your educated guess—you can ask for additional hints, too. [Leaving a comment is easy; just click the ‘Leave a comment’ at the end of the post and fill in the form. If it’s the first time you post a comment, it will be held for moderation. But I am constantly checking, and once I’ve approved a comment, your next ones won’t be held, but published immediately by the system.]

UPDATE and solution (20 December 2011):

↵Well done, ryoku, and, yes, it is ↑Michael Rennie‘s arm, or the arm of the character Garth A7 Rennie plays in the movie ‘↑Cyborg 2087‘ (Adreon 1966). The actor’s name should ring a big bell within every science fiction enthusiast, because Rennie played ‘Klaatu’ in the classic ‘↑The Day the Earth stood still‘ (Wise 1951), later ↑remade (Derrickson 2008) with Keanu Reeves as the lead. Before that Rennie already was made immortal in the first song of Richard O’Brien’s ‘↑The Rocky Horror Picture Show‘ (Sharman 1975). The song ‘Science Fiction Double Feature’ begins thus: ‘Michael Rennie was ill the day the Earth stood still. But he told us where we stand.’

In his winning comment ryoku also asked: ‘But seriously. Who would know such a movie?’

Well, James Cameron would, I guess.

My next hint would have been: In the scene the arm is revealed and shown in order to proof a point. But allow me to start from the beginning.

In the year 2087 a totalitarian regime reigns planet Earth. Total social control is achieved by ‘radio telepathy.’ A resistance group manages to send the cyborg Garth (Michael Rennie) back through time into the year 1966.

Garth’s mission is to find Professor Sigmund Marx (Eduard Franz), the inventor of radio telepathy, and to take him out of the course of history. Either by persuading him to come with Garth into the time machine, or by killing him. That way radio telepathy would not be invented, and humankind would not be enslaved later on.

Having arrived in 1966 Garth reaches the Professor’s laboratory at ‘Future Industries Inc.’ (the company’s tag line is: ‘Research today for a better tomorrow’) Their he encounters Marx’s assistant, Dr. Sharon Mason (Karen Steele). Using the prototype of the radio telepathy machine Garth ‘persuades’ Dr. Mason that he is a cyborg from the future who has to find Professor Marx in order to save mankind.

Time is pressing, because there is a problem. Garth carries an emitter implanted in his chest. The device’s signal allows the future totalitarian government to locate him through time and space. And indeed action already has been taken. Two other cyborgs, called ‘Tracers,’ have been sent back to 1966. Their mission is to hunt down and destroy Garth. Hence he has to get rid of the device in his chest as soon as possible.

Sounds a lot like ‘↑Terminator 2: Judgement Day‘ (Cameron 1991), doesn’t it? But the similarities are not limited to the plot.

Dr. Steele brings Garth to Dr. Carl Zeller (Warren Stevens), a surgeon, whom they tell the whole story, and then ask him to surgically remove the emitter. Naturally Dr. Zeller is reluctant to believe in the phantastic tale. So Garth roles up his sleeve and shows Dr. Zeller that he indeed is a man-machine hybrid.

Dr. Zeller removes the emitter, alas, the Tracers already are too close. A dramatic showdown unfolds, but in the end Garth overcomes the tracers—and develops romantic feelings for Sharon. An unheard of thing for a cyborg.

Meanwhile Professor Marx has returned from a lecture he has delivered. He quickly gets what Garth explains to him and agrees to join him in the time machine. The very moment the machine disappears with its passengers, the time-travel paradoxon kicks in. Nothing of the movie’s story has ever happened and in consequence the memories of the events in an instant are erased from the minds of all protagonists in the year 1966—but James Cameron didn’t forget ;-)

the machine stops

‘↓The Machine Stops‘ is a science fiction short story or novella by ↑E. M. Forster, first published in 1909. Here is the story’s setting as ↑Wikipedia’s plot summary has it:

The story describes a world in which most of the human population has lost the ability to live on the surface of the Earth. Each individual now lives in isolation below ground in a standard ‘cell’, with all bodily and spiritual needs met by the omnipotent, global Machine. Travel is permitted but unpopular and rarely necessary. Communication is made via a kind of instant messaging/video conferencing machine called the speaking apparatus, with which people conduct their only activity, the sharing of ideas and knowledge.

Sounds familiar? Remember: The story was originally published in 1909!

In 1966 the BBC aired a television adaptation (see above) as the first episode of the second season of the science fiction series ‘↑Out of the Unknown.’ The ↑episodes listing shows that for the series stories by an impressive roster of New Wave Science Fiction authors were adapted.

call for the dead

[…] academic excursions into the mystery of human behaviour, disciplined by the practical application of his own deductions. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 1)

This part of him was bloodless and inhuman—Smiley in this role was the international mercenary of his trade, amoral and without motive beyond that of personal gratification. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 1)

By the strength of his intellect, he forced himself to observe humanity with clinical objectivity, and because he was neither immortal nor infallible he hated and feared the falseness of life. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 1)

For four years he had played the part, travelling back and forth between Switzerland, Germany and Sweden. He had never guessed it was possible to be frightened for so long. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 1)

The warmth was contraband, smuggled from his bed and hoarded against the wet January night. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 2)

A slight, fierce woman in her fifties with hair cut very short and dyed to the colour of nicotine. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 3)

‘My body and I must put up with one another twenty hours a day. […]‘ (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 4)

And back to the unreality of containing a human tragedy in a three-page report. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 4)

[…] he would spend the afternoon pursuing Olearius across the Russian continent on his Hansa voyage. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 5)

He wanted to explain why it was impossible to understand nineteenth-century Europe without a working knowledge of the naturalistic sciences, […]. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 6)

He hated the bed as a drowning man hates the sea. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 8)

He used to say that the greatest mistake man ever made was to distinguish between the mind and the body: an order does not exist if it is not obeyed. He used to quote Kleist a great deal: ‘if all eyes were made of green glass, and if all that seems white was really green, who would be the wiser?’ Something like that. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 11)

Smiley hugged his greatcoat round him […]. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 11)

Mundt had proceeded with the inflexibility of a trained mercenary—efficient, purposeful, narrow. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 14)

Oriental dance, where the tiny gestures of hand and foot animate a motionless body. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 15)

He was one of those world-builders who seem to do nothing but destroy […]. (Le Carré 1961: chpt. 16)

cyberpunk listings update

The lists of cyberpunkish artefacts in the menu ↵cyberpunk (see above) still are (and forever will be :-) work in progress, but I heavily updated them. The last days I was down with some kind of flu, hence couldn’t concentrate on harder tasks anyway, and so gave it a go. First I added a lot of movies to the ↵motion pictures list—in fact every single movie ↑Emily E. Auger calls ↵tech noir. In other words: I cannibalized her wonderful book (2011). Next I introduced two subcategories: ↵television and ↵video. In consequence the motion pictures list now only features movies which indeed have been released to the cinemas.