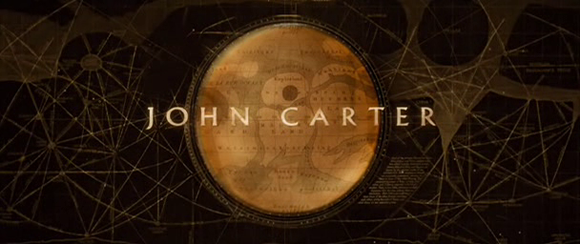

zeph’s pop culture quiz #47

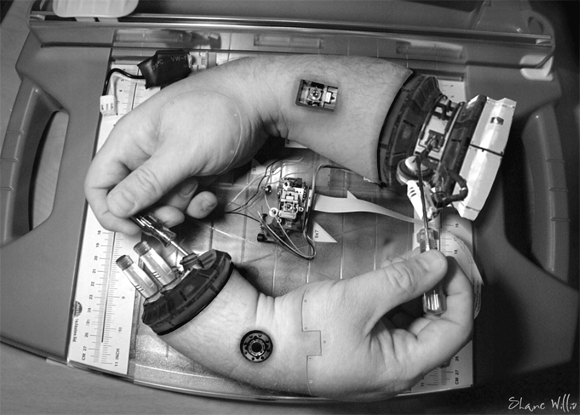

Between which worlds is the man the depicted hand belongs to travelling?

Just leave a comment with your educated guess—you can ask for additional hints, too. [Leaving a comment is easy; just click the ‘Leave a comment’ at the end of the post and fill in the form. If it’s the first time you post a comment, it will be held for moderation. But I am constantly checking, and once I’ve approved a comment, your next ones won’t be held, but published immediately by the system.]

UPDATE and solution (31 October 2012):

This was a slip, I have to confess. Normally, before I post a quiz, I check for the most obvious search terms, so that the riddle isn’t solved too fast by the help of mere technological assistance. This time I omitted that step. Maybe because I found the title ‘between which worlds?’ just too compelling. Anyhow, that way ↵Alhambra immediately solved #47. Without having seen the movie, and without ever even having heard of it, as she confessed to me via e-mail. Congratulations nevertheless—‘↑John Carter‘ (Stanton 2012) it is! And here is yet another slip of mine: In the movie the hand doesn’t belong to Carter (Taylor Kitsch), but to his nephew Edgar Rice Burroughs (Daryl Sabara).

The movie is largely based on the novel ‘↑A Princess of Mars‘ (1917 [1912]) by ↑Edgar Rice Burroughs, who also invented ↑Tarzan. As a homage the character of Burroughs as Carter’s nephew was put into the 2012 movie’s script. ‘A Princess of Mars,’ originally published in serialized form as ‘Under the Moons of Mars,’ was the very first story Burroughs wrote. All in all ten sequel novels followed, telling the adventures of John Carter and his offspring. Although not the first of its kind, the ‘Barsoom series’—’Barsoom’ being the ‘indigenous’ name of the planet we call ‘Mars’—is an early, well known, and very influential ↑planetary romance (a peculiar fusion of science fiction and fantasy). Another well known example are the adventures of ↑Flash Gordon, from whom we just recently heard two times (↵what is this? and the ↵the flash inspirations). While Gordon travels from Earth to the planet Mongo the ‘conventional way,’ by rocket ship that is, John Carter seems to be teleported from Earth, from the Arizona Hills to be precise, to Mars by an, at first, inexplicable force. In the novel this happens at the end of the second, and the beginning of the third chapter:

As I stood thus meditating, I turned my gaze from the landscape to the heavens where the myriad stars formed a gorgeous and fitting canopy for the wonders of the earthly scene. My attention was quickly riveted by a large red star close to the distant horizon. As I gazed upon it I felt a spell of overpowering fascination—it was Mars, the god of war, and for me, the fighting man, it had always held the power of irresistible enchantment. As I gazed at it on that far-gone night it seemed to call across the unthinkable void, to lure me to it, to draw me as the lodestone attracts a particle of iron.

My longing was beyond the power of opposition; I closed my eyes, stretched out my arms toward the god of my vocation and felt myself drawn with the suddenness of thought through the trackless immensity of space. There was an instant of extreme cold and utter darkness. (Burroughs 1917 [1912]: chpt. 2)

I opened my eyes upon a strange and weird landscape. I knew that I was on Mars; not once did I question either my sanity or my wakefulness. I was not asleep, no need for pinching here; my inner consciousness told me as plainly that I was upon Mars as your conscious mind tells you that you are upon Earth. You do not question the fact; neither did I.

(Burroughs 1917 [1912]: chpt. 3)

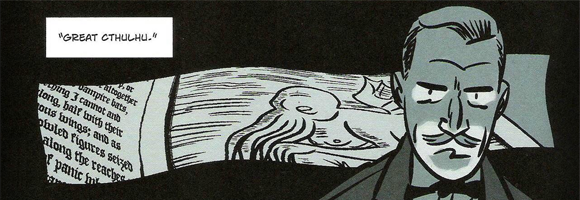

Another planetary romance, which I read as a teenager and admire until today, is the epic graphic novel saga around the hero ‘↑Den‘ by ↑Richard Corben—very much inspired by John Carter of Mars [and by ↑Lovecraft—a cosmic demon god in the world of Neverwhere is called ↑Uluhtc …]:

Then it came to me. My name is … was David Ellis Norman. I was mourning my Uncle Daniel’s death. They had never found him but now, after seven years it was legal. Some of his belongings had come into my possession including his collection of Burroughs fantasy novels. In the back of one was a piece of paper with an electronic schematic on it … there was also a letter … addressed to me. (Corben 1977-1978, part 2: 49)

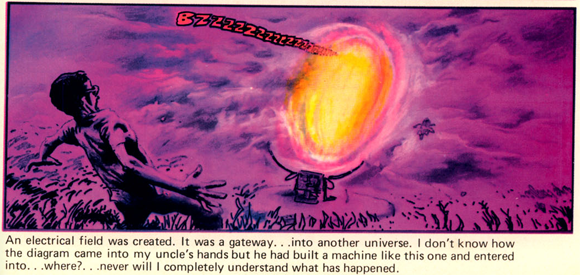

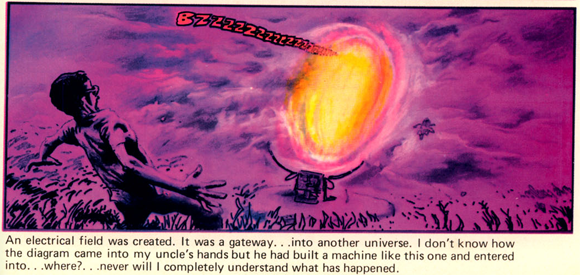

David decides to build the device described by the plans of his uncle, takes it ‘to an abandoned farm area’ and tries it out:

David Ellis Norman trying out the device he built by the plans his uncle left to him (Corben 1977-1978, part 2: 50)

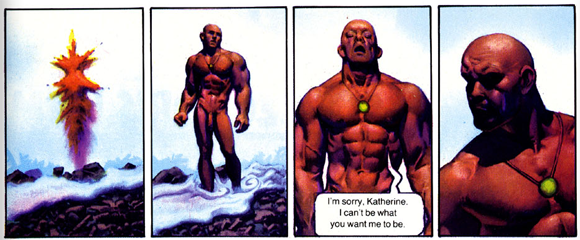

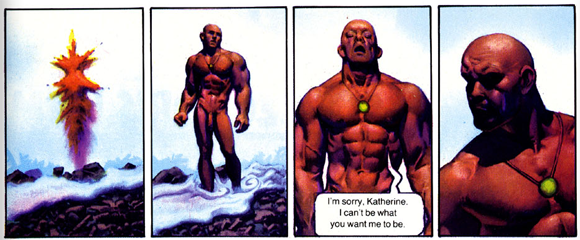

Planetary romances, sometimes even dubbed as the ‘↑sword and planet‘ genre, of course are not cyberpunk at all. But it is remarkable, I think, that during the historical treshold, when the ↵cyberpunk discourse became manifest as a literary genre, Richard Corben integrated technology into the saga of Den, with otherwise comprises fantasy and the downright supernatural: David Ellis Norman is transported from Earth to Neverwhere, and is transformed into Den, by a force or principle which can be made to work by both electronics and magic:

David Ellis Norman for the second time spawning in Neverwhere as ‘Den’ (Corben 1981-1983, part 6: 89). This time he presumably didn’t travel by the means of technoscience, but made his journey using magic—mind the amulet around his neck.

In this I sense something similar like in the story about ↵how the cyberpunk discourse infested the zombie genre.

BURROUGHS, EDGAR RICE. 1917 [1912]. A princess of Mars. Chicago: A. C. McClurg. First serialized as Under the moons of Mars in The All-Story.

CORBEN, RICHARD. 1977-1978. Den. Heavy Metal 1(1): 5-12, 1(2): 45-52, 1(3): 45-52, 1(4): 12-18, 1(5): 9-17, 1(6): 9-17, 1(7): 45-52, 1(8): 9-16, 1(9): 7-14, 1(10): 33-40, 1(11): 9-16, 1(12): 7-14, and 1(13): 6-13.

CORBEN, RICHARD. 1981-1983. Den II. Heavy Metal 5(6): 6-15, 5(7): 33-40, 5(9): 17-24, 5(10): 76-79, 5(11): 39-42, 5(12): 84-89, 6(1): 21-24, 6(2): 21-24. 6(3): 20-23, 6(4): 12-16, 6(5): 73-76, 6(6): 19-24, 6(7): 19-24, 6(8): 20-25, 6(9): 36-41, 6(10): 78-86, 6(11): 14-20, and 6(12): 37-43.

STANTON, ANDREW. 2012. John Carter [motion picture]. Burbank: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

![mountains_of_madness Detail of the cover of Astounding Stories 16(6) [February 1936]. Art by Howard V. Brown.](http://xirdalium.net/wp-content/uploads/mountains_of_madness.png)