archæology of steampunk

Just a minute ago I pre-ordered ‘Steampunk: kurz & geek’ (Jahnke & Rauchfuß 2012) after I had read ↑Kueperpunk’s review (he has a reviewer’s copy). It reminded me of Ekaterina Sedia’s introduction (Sedia 2012) in ‘The Mammoth Book of Steampunk’ (Wallace 2012):

With the recent release of ↑The Steampunk Bible (ed. Jeff VanderMeer and SJ Chambers [2011]), it seems that steampunk as a genre finally came into its own and has grown enough to demand its own compendium, summarizing various parts of this remarkably protean movement, and pointing out interesting things happening in its DIY culture, cosplay, film, literature and music. The fact that the steampunk esthetic penetrates all aspects and art forms indicates that it is remarkably malleable and yet recognizable. We often see steampunk as gears and goggles glued to top hats, but this impression is of course superficial, and there is much more complexity to the fashion and maker aspects of it – just take a look at the Steampunk Workshop website by Jake Von Slatt if you don’t believe me! And yet, much like pornography, all of these expressions conform to a common pattern – difficult to describe beyond the superficial, but one just knows it when one sees it. (Sedia 2012: 1)

When we try to grasp steampunk in the sense of Foucault’s ‘Archaeology of Knowledge’ (Foucault 1972 [1969]) the ‘common pattern’ and the ↵concept of the technologically driven alternative course of history becomes tangible, I guess. Additionally effects like steampunk’s ↵spilling over to Latin America become understandable, too.

technology, society, and the scope of anthropology

The ↓next biannual conference of the German Anthropological Association (↑GAA) will take place exactly one year from today, from 2nd to 5th October 2013, in Mainz, Germany. I am organizing a workshop there, called ‘Technology, society, and the scope of anthropology.’ The official call for papers will be sent out by the GAA around end of this month, but here you already have it:

Technologies like—for example, but not exclusively—digital electronics in all its guises, on the one hand permeate everyday life on a global scale and at an accelerating pace. On the other hand, hardly surprising, those are omnipresent in societal, political, economic, and artistic discourses. Anthropology has not been blind to this. In recent years more and more work is done wherein technologies play decisive roles, the genre media anthropology meanwhile is consolidated, and so on. In spite of that the anthropological voice still does not thunder in public discourses (exceptions like e.g. David Graeber granted), which is lamented by the profession. Inconsistently an anthropological spill-over into larger and public circles seems to be contained and repressed by the anthropologists themselves. At the same time there are proponents who wholeheartedly embrace our discipline and push it to the forefront. It is significant that Bruno Latour, whose voice definitely is heard widely, not only clearly communicates to be tremendously fond of anthropology, but even suggests a fusion of anthropology and science and technology studies. This way, he hopes, the dichotomy of nature and culture/society, and differentiations between pre-modern, modern, and postmodern, can be transcended. Ultimately interpretations of our world could be gained which are highly uncontaminated by all kinds of -centrisms, and thus would be of the highest value for discourses outside of academia. With the nexus technology, society, and culture as a point of origin the workshop’s aim is to discuss the unique potentials of anthropology to 1) help to understand our technology-drenched world in global, local, and historical dimensions, 2) to communicate this knowledge and to feed it into public discourses, and 3) to prepare students for jobs in this very world—within and without anthropology.

Those interested to present there are hereby invited to send me a proposal (200 words max.) by email, to alexander[dot]knorr[at]lmu[dot]de, before the end of January 2013.

who is exchanged?

zeph’s pop culture quiz #44

Here is a fine noir Cold War scenario. Right at the Iron Curtain government officials are waiting for an exchange of prisoners. But who is exchanged?

Just leave a comment with your educated guess—you can ask for additional hints, too. [Leaving a comment is easy; just click the ‘Leave a comment’ at the end of the post and fill in the form. If it’s the first time you post a comment, it will be held for moderation. But I am constantly checking, and once I’ve approved a comment, your next ones won’t be held, but published immediately by the system.]

UPDATE and solution (03 October 2012):

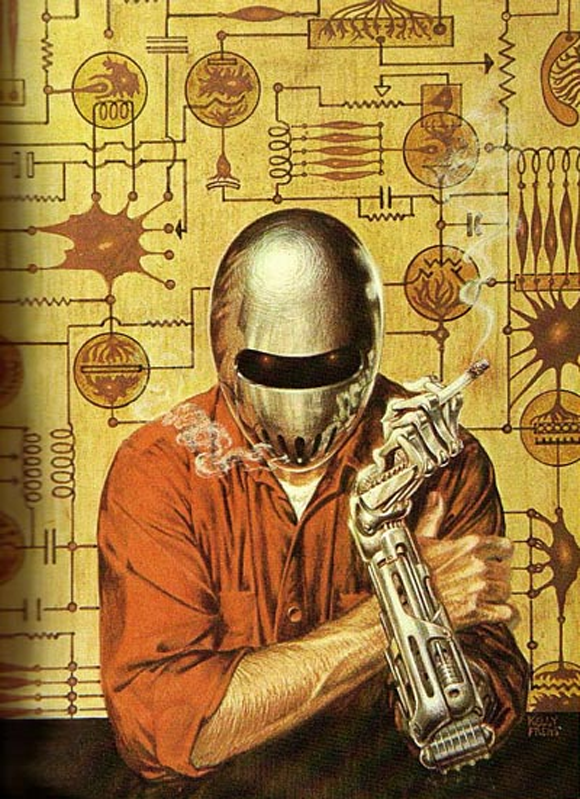

Again ↑Kueperpunk ↵did it, as it seems on first glance. The screencap was taken early into ‘Who?’ (Gold 1973). Allied government officials are waiting for the scientist Dr. Lucas Martino (Joseph Bova) to cross ‘the line’—the Iron Curtain—and return from the soviet to the allied zone. Among those waiting is the security agent Sean Rogers (Elliott Gould). At the negotiated time a man indeed comes over, but he has been turned into a cyborg. His left arm and his head now are made of metal.

The movie is based on a novel of the same name by ↑Algis Budrys (1958). Here is the begining of the novel, describing the scene depicted in the screencaps:

It was near the middle of the night. The wind came up from the river, moaning under the filigreed iron bridges, and the weathercocks on the dark old buildings pointed their heads north.

The Military Police sergeant in charge had lined up his receiving squad on either side of the cobbled street. Blocking the street was a weathered concrete gateway with a black-and-white-striped wooden rail. The headlights of the MP super-Jeeps and of the waiting Allied Nations Government sedan glinted from the raised shatterproof riot visors on the squad’s varnished helmets. Over their heads was a sign, fluorescing in the lights:

YOU ARE LEAVING THE ALLIED SPHERE

YOU ARE ENTERING THE SOVIET SOCIALIST SPHERE

In the parked sedan, Shawn Rogers sat waiting with a man from the ANG Foreign Ministry beside him. Rogers was Security Chief for this sector of the ANG administered Central European Frontier District. He waited patiently, his light green eyes brooding in the dark.

The Foreign Ministry representative looked at his thin gold wristwatch. “They’ll be here with him in a minute.” He drummed his fingertips on his briefcase. “If they keep to their schedule.” […]

The war was in all the world’s filing cabinets. The weapon was information: things you knew, things you’d found out about them, things they knew about you. You sent people over the line, or you had them planted from years ago, and you probed. Not many of your people got through. Some of them might. So you put together the little scraps of what you’d found out, hoping it wasn’t too garbled, and in the end, if you were clever, you knew what the Soviets were going to do next. […]

Out beyond the gateway, two headlights bloomed up, turned sideward, and stopped. The rear door of a Tatra limousine snapped open, and at the same time one of the Soviet guards went over to the gate and flipped the rail up. The Allied MP sergeant called his men to attention.

Rogers and the Foreign Ministry representative got out of their car.

A man stepped out of the Tatra and came to the gateway. He hesitated at the border and then walked forward quickly between the two rows of MP’s.

“Good God!” the Foreign Ministry man whispered.

The lights glittered in a spray of bluish reflection from the man in the gateway. He was mostly metal. (Budrys 1958: part 1, chpt. 1)

A bit later, the ‘man with the steel mask’ has been brought to an allied facility, Rogers has to report to his superior by telephone. When he is asked if everything went all right with Martion, Rogers answers no, and asks for an emergency team comprising experts on miniature mechanical devices, surveillance, and a psychologist. Finally Mr. Deptford, Rogers’ superior asks: ‘Rogers—did Martino come over the line tonight or didn’t he?’ Rogers hesitates briefly and then can only answer: ‘I don’t know’ (Budrys 1958: part 1, chpt. 2). And indeed the whole story unfolding is about the question if the technologically enhanced man who came over the line is Martino or not.

The movie is quite faithful to the novel, nevertheless there are differences. In the novel Dr. Martino had worked in a laboratory in ‘the West’ which was located close to the Iron Curtain. Quite at the beginning of the novel this already is criticized by a representative of the foreign ministry: ‘Why the devil did we give Martino a laboratory so near the border in the first place?’ (Budrys 1958: part 1, chpt. 1) An accident with subsequent explosion took place there. In the immediate wake of it a soviet team from right across the border was faster to recover Martino than the allied rescue team. That way he came into the soviet zone, heavily injured. His cyborg parts are the result of the soviet scientist’s effort to save him. In the movie the laboratory incident has been replaced by a car accident close to the border, resulting from a very B-movie version of a car chase.

From a 1958 perspective the novel is set in a probable near future, not just because of the obviously advanced soviet technology. In the world of ‘Who?’ the Soviet Union has fused with the People’s Republic of China and the so called Free World has fused to a megastate as well. From a 2012 retrospective it’s an alternate history, of course. For the 1973 movie version this setting has been toned down, and the historical world map has been retained.

All in all both, novel and movie, are fusions of a psychological cold war espionage thriller spy game and a cyberpunkish coin of science fiction. So ‘Who?’ perfectly fits into ↵the cyberpunk discourse.

arab spring media

My friend ↑Vít Šisler just notified me via email that ↑CyberOrient 6(1) is out. Vít writes:

[The new issue] aims for critical and evidence-based evaluation of the use of social media in the Arab Spring, the coverage of the Arab Spring in cyberspace and beyond, and the remediation and appropriation between social media and traditional media outlets, including satellite TVs and the press.

See also ↵anthropologists on egypt, ↵irevolution in bahrain, and especially ↵heretics house tripoli and its follow-up ↵teliasonera’s black boxes. For those into computer games, check out ↑Vít’s publications, ↵computer games, Islam, and politics, and ↵tahta al-hisar—under siege.

talking science studies

This comes very handy as I am right now putting the final touches to the class ‘Science and Technology Studies’ which I’ll deliver the coming semester: Thomas Lohninger, founder of, and force behind ↑Talking Anthropology, has done an interview on science studies with ↑Ulrike Felt: ↓TA43—Wissenschaftsforschung [in German | 01:55:54]. I haven’t listened to it yet, but the comprehensive description and given links do look very promising. Hopefully the two hours are suited as introductory material for the students.

This comes very handy as I am right now putting the final touches to the class ‘Science and Technology Studies’ which I’ll deliver the coming semester: Thomas Lohninger, founder of, and force behind ↑Talking Anthropology, has done an interview on science studies with ↑Ulrike Felt: ↓TA43—Wissenschaftsforschung [in German | 01:55:54]. I haven’t listened to it yet, but the comprehensive description and given links do look very promising. Hopefully the two hours are suited as introductory material for the students.

harper goff’s nautilus

Just recently we heard that ↵the mash still is safe and sound at the Smithsonian—now there’s even more comforting news. The original model of ↵Captain Nemo’s submarine ‘Nautilus’ designed by ↑Harper Goff and used in ‘↑20,000 Leagues Under The Sea‘ by Richard Fleischer (1954) is kept intact ↑at the Disney Archives.

space aircraft carriers

↑Christopher Weuve, among other things a naval analyst and science fiction geek, ↑talked with Michael Peck of Foreign Policy about the dialectics between naval warfare and space warfare as depicted in science fiction. When Peck asked, “Has sci-fi affected the way that our navies conduct warfare?” Weuve answered:

This is a question that I occasionally think about. Many people point to the development of the shipboard Combat Information Center in World War II as being inspired by E.E. Doc Smith’s Lensman novels from the 1940s [Smith 1950 [1937]]. Smith realized that with hundreds of ships over huge expanses, the mere act of coordinating them was problematic. I think there is a synergistic effect. I also know a number of naval officers who have admitted to me that the reason they joined the Navy was because Starfleet Command wasn’t hiring.

That last sentence reminded me of Karl Taro Greenfeld’s main informant concerning the Bosozoku:

He had seen the Midnight Angels around and was dazzled by their loud motorcycles, gaudy cars, and kamikaze outfits; as they rode Arakawa Ward they reminded him of the kind of delinquents who were the heros in Akira [Otomo 1982-1990], his favorite comic book. So Tats[uhiro Nobutani] joined. (Greenfeld 1994: 24)

So, Appadurai is more right than ever when he insists that fictional material in our times offers a multitude of inspirations for biographies. And I insist that science fiction is most crucial in this. The whole interview with Chris Weuve is very worthwhile; here is his closing paragraph:

Fiction does not replace policy analysis. But science fiction is the literature of “what if?” Not just “what if X happens?” but also “what if we continue what we’re doing?” In that way, science fiction can inform policy making directly, and it can inform those who build scenarios for wargames and exercises and the like. One of the great strengths of science fiction is that it allows you have a conversation about something that you otherwise couldn’t talk about because it’s too politically charged. It allows you to create the universe you need in order to have the conversation you want to have. Battlestar Galactica spent a lot of time talking about the war in Iraq. There were lots of things on that show about how you treat prisoners. They never came out and said that directly. They didn’t have to. At the Naval War College, one of the core courses on strategy and policy had a section on the Peloponnesian War. It was added to the curriculum in the mid-1970s because the Vietnam War was too close, so they couldn’t talk about it, except by going back to 400 BC.

wolfenstein 3d online

At ↑Tom Hall’s weblog I ↑read that Bethesda has celebrated the 20th birthday of ‘Wolfenstein 3D’ (id Software 1992) by putting it online as a free browser game. But when I clicked ↑the link I got a 404—it ain’t here anymore. Either Bethesda has taken it offline again, or the fabulous German banning mechanisms kicked in. I am too lazy to go via proxy, especially because there’s another solution. At Virtual Apple you can ↑play that milestone of computer game history via an Apple ][ emulation.

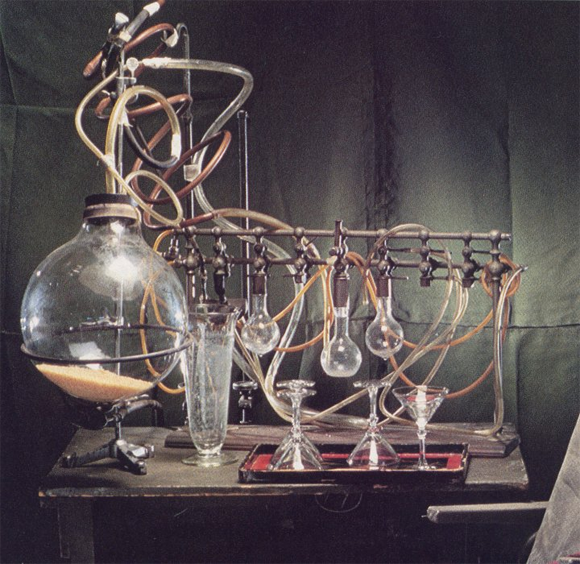

the mash still

After the ↵infamous Stim-U-Lax [and after just recently having spoken of ↵wonderful contraptions] here’s another piece of weird technology from ↑M*A*S*H: ↑the still!

Following the end of production on M*A*S*H in January of 1983, 20th Century-Fox donated the O.R. set and the Swamp set to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Included was the still. An exhibition was held at the National Museum of American History from July of 1983 to January of 1985. When the exhibition closed, the sets were packed up and placed in storage. The still is likely in a box somewhere in a warehouse.