cyberculture as discourse

After elaborating on methodological concerns and before delving into detailed analysis of the representational politics in selected cyberpop examples, it is important to situate the objects of this book in their cultural context. Chapter 2 is an overview of several key concepts in the network of discourses and practices that constitute cyberculture and, by extension, its popular media productions. Describing cyberculture as a discursive formation (inspired by theories of Michel Foucault (Archeology) helpfully clarifies how the key concepts that emerge repeatedly in cyberpop operate as a network or conceptual architecture linking technologies to individual subjects, identities, and digital lifestyles. In order to provide a framework for the analysis that follows then, we explicate in detail three of the rules of formation that operate in cyberculture: namely, intangibility, connectivity, and speed. Examining magazine advertisements for digital products and services, and e-commerce management literature advising audiences on how to succeed in “the connected economy,” reveals the same collection of key concepts (or rules) used to promote digital capitalist culture, and the development of compatible identities and lifestyles. (Matrix 2006: 5-6)

kajola

where is he?

zeph’s pop culture quiz #22

Strange landscape, isn’t it? Where is the lonely wanderer?

Just leave a comment with your educated guess—you can ask for additional hints, too. [Leaving a comment is easy; just click the ‘Leave a comment’ at the end of the post and fill in the form. If it’s the first time you post a comment, it will be held for moderation. But I am constantly checking, and once I’ve approved a comment, your next ones won’t be held, but published immediately by the system.]

UPDATE and solution (02 April 2012):

That one obviously was way ↵too easy for Mr Rabitsch, our resident connaisseur. Yes, Todd (Kurt Russell) is on Arcadia 234, a planet used for waste disposal on which most of the plot of the 1998 movie ‘Soldier’ takes place. It was directed by Paul W. S. ‘Resident Evil’ Anderson and written by David Peoples. The latter, together with Hampton Fancher, made Philip K. Dick’s novel ‘Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?’ (1968) into the script of ‘Blade Runner’ (Scott 1982). In fact ‘Soldier’ is set in the same universe as ‘Blade Runner’ and a lot of allusions try to establish this. But, and that’s my opinion, the story falls flat and is in no way on par with ‘Blade Runner.’ On the other hand parts of the movie’s visuals succeed in establishing a cyberpunkish ambience—like the magnificent vista with the dumped aircraft carrier above.

dislocation

The Tamil-movie ↵Endhiran (Shankar 2010) is testimony of the cyberpunk discourse having reached Indian cinema. Nigeria’s Yoruba-language ‘Kajola’ (Akinmolayan 2010) shows the ↵same for Africa‘s largest movie industry.

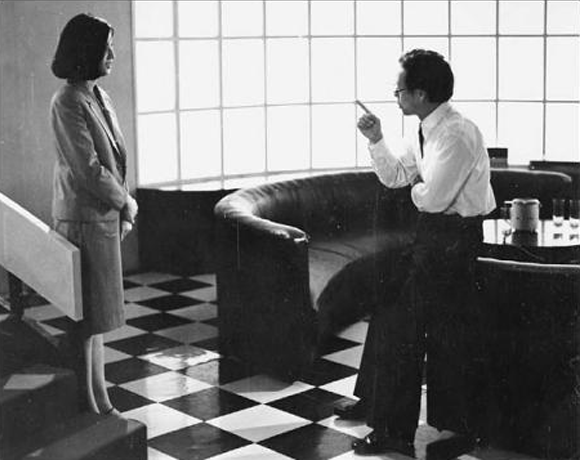

‘Science-fiction film, like the science-fiction story, is an underdeveloped genre in China,’ writes Yingjin Zhang (1998: 297) in the ‘Encyclopedia of Chinese Film’ (Zhang & Xiao 1998). Nevertheless, already during the heyday of canonical [US-] cyberpunk there was a chinese cyberpunk movie—‘Dislocation’ directed by Huang Jianxin (1986).

As with Huang’s first film, Black Cannon Incident [1985], Dislocation uses the science-fiction genre to satirize the workings of bureaucracy. The protagonist, Zhao Shuxin, this time the director of a large department, suffers a series of nightmares. The absurd world that he dreams of signifies China in its socialist heyday, while the everyday world he inhabits represents China’s near future. A corrupt social system everywhere undermines technological innovation. Zhao longs for peace of mind and seeks a high tech solution, which unfortunately backfires.

In a skyscraper-filled urban setting, an isolated human figure surrounded by microphones and almost buried by files struggles with a socialist bureaucratic phenomenon: endless and meaningless talks and meetings. The use of red filters and shrill noises on the soundtrack reinforce the sense of unbearable conditions. The character wakes up from this operating room nightmare in which medical staff in black uniforms are attempting to kill him.

Contemplating himself in the mirror inspires Zhao to design a robot. Made in his image, the robot could stand in for him at every boring meeting. The robot should be a mechanical object subject to human instruction by its master. Yet Robot Zhao likes to attend meetings and give talks. It even learns how to smoke and drink. A visual montage of wine cups, cameras, and futuristic buildings, accompanied by the sound of applause, portrays the world the robot comes to enjoy.

Conflicts between human and machine emerge. During a conversation, robot Zhao expresses its concern that humans issue so many rules they then expect others to obey. Director Zhao warns the machine: ‘You think too much. That’s dangerous’.

The conflicts escalate as the robot becomes addicted to the systemic corruptions of modern living. Away from its master, it dates Zhao’s girlfriend, seducing her by offering her Zhao’s house key. He humiliates people with threats of violence. When Zhao expresses his desire to assign the robot a job doing work that is too dangerous for humans, the robot rebels by exposing itself in front of its designer. At last, in a final power struggle, Zhao destroys the robot. As Zhao looks again into the mirror, his nightmares begin anew. (Cui 1998: 143)

playing with videogames

[abstract:] Playing with Videogames documents the richly productive, playful and social cultures of videogaming that support, surround and sustain this most important of digital media forms and yet which remain largely invisible within existing studies. James Newman details the rich array of activities that surround game-playing, charting the vibrant and productive practices of the vast number of videogame players and the extensive ‘shadow’ economy of walkthroughs, FAQs, art, narratives, online discussion boards and fan games, as well as the cultures of cheating, copying and piracy that have emerged.

Playing with Videogames offers the reader a comprehensive understanding of the meanings of videogames and videogaming within the contemporary media environment.

sentry gun redux

Some things won’t lose their fascination—especially when a certain morbidness is involved, as it seems. Just the day before yesterday boingboing’s ↑Mark Frauenfelder pointed to Bob Rudolph’s ↑project sentry gun, an open-source sentry gun controller. Well, seven years ago ↵on xirdalium I reported Aaron Rasmussen’s ‘quintessential sentry gun.’ As far as I can see all his websites meanwhile have vanished—I only found the 2006 article ↑Sentry gun sees, computes and shoots at BU [Boston University] Today, which gives an idea towards where Aaron may have headed, plus refound his original document [lavishly illustrated] ↓How we built the quintessential sentry gun [.pdf | 342KB]. Quite matching: my old article ↵robots and suicide bombing …

magic kingdom pilgrimage

[abstract:] This essay explores the proposition that Walt Disney World is an amusement park whose form is borrowed from the pilgrimage center. Bateson, Norbeck, and Turner have shown that play and ritual together comprise a metaprocess of expressive behavior rooted in our mammalian past. Substantively both traditional pilgrimage centers, especially Mecca, and Walt Disney World are analyzed in terms of shared activities, symbols displayed, myths evoked, and tripartite time-space processes of rites of passage. The Magic Kingdom is shown to be a giant limen ritual threshold, which symbolically replicates the baroque capital. To go there is to engage in transcendent make-believe, play which is intended with deadly seriousness. The pilgrimage form has re-emerged as a place for grand play. Finally, the essay speculates that the playful pilgrimage is particularly appropriate to a secular, technologized society in which transition is constant.

material cyberculture

[abstract:] This essay offers a polemical exploration of spatiality in new media culture, one based on a materialist, as opposed to a ‘ virtualist’ paradigm. Its goal is to intervene in the thought processes of liberal-phenomenological cybertheory. The latter tends to see computer users as consumers, rather than producers, within national and global economies. Because of this leisure-consumption orien tation, theories of new media are easily appropriated within ideologies of postindustrial capitalism. This has led to some oversimplified models of spatiality in cybertheory, many of which proceed from the premise that the material world is fast disappearing under the pressures and seductions of the virtual. The article uses methods of visual anthropology to communicate the problems with such as sumptions, and to demonstrate the benefits of materialist analysis. It traces the techniques information and knowledge workers use in fashioning decorative office media displays, known in cyber jargon as ‘geekospheres’. These techniques situate the computer within the labor process, not only as a tool but also as a physical object through which people make statements about work and find ways to define and transgress boundaries between the personal and the institutional, between work and leisure.

cues in cyberspace

[abstract:] Although the relative paucity of social cues in computer-mediated communication poses problems of the organization of social relations in cyberspace, recent studies have begun to focus on the ways in whicht this deficit is managed. This article contributes to this research by addressing the question of how participants distinguish between contexts in online discourse. Data on cues, and on naming practices in particular, in text-based virtual realities called MOOs illustrate the structure of contexts and the dynamics of contextualizing communication and interaction in cyberspace.