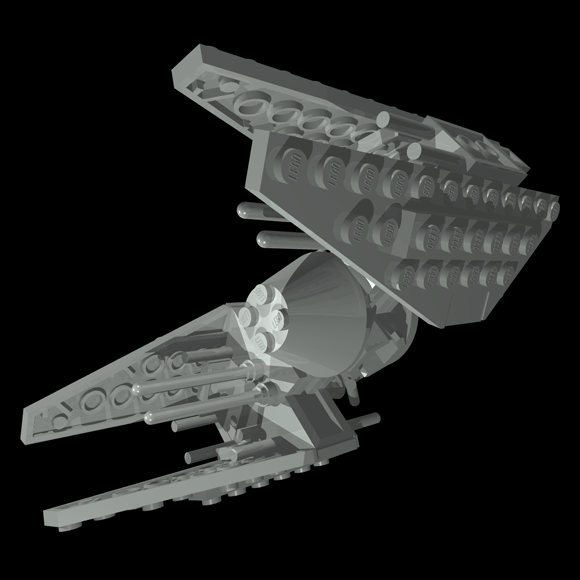

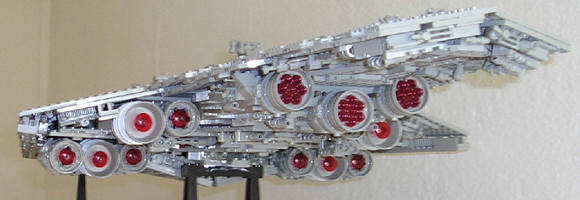

It seems like I can’t resist the gravity of the vast ↵moc- and afol-scene. And thick participation means, among other things, sharing practices. So I followed the comprehensive tutorial ↑Converting LDR Files to POV Files for Rendering by Jeroen de Haan and Jake McKee and then ran my rendition of a ↑TIE Interceptor (which I built first in the flesh, and then with the ↑LDraw-based ↑MLCad) through ↑POVRay. All that reminded me very much of ye olde days of game modding. Here’s how my model (every single part of it stems from the 1970s!) looks in meatspace:

cyberanthropology

My new book ‘↑Cyberanthropology‘ has been published. You absolutely are invited to order it online ↑via amazon [I have absolutely nothing against you clicking the like-button there] or ↑via Peter Hammer Verlag. Offline every decent bookshop can get it for you, too. As the book is in German, here is my description of its contents in German:

My new book ‘↑Cyberanthropology‘ has been published. You absolutely are invited to order it online ↑via amazon [I have absolutely nothing against you clicking the like-button there] or ↑via Peter Hammer Verlag. Offline every decent bookshop can get it for you, too. As the book is in German, here is my description of its contents in German:

In “Cyberanthropology” geht es um moderne Technik und den Menschen, um Computer und Internet, um Computerspiele, aber auch um GPS, Automobile, Roboter …

Was vor nicht allzu langer Zeit Science Fiction war, ist Lebenswirklichkeit geworden. Die vielfältigen Erscheinungsformen digitaler Elektronik und modernster Technik allgemein bestimmen unsere heutige Welt ganz entscheidend mit. Überall auf dem Globus sind sie zu Faktoren des menschlichen Daseins geworden. Viele der auf der Welt zu findenden Vorstellungen und Entwürfe, mit diesem Dasein umzugehen, lösen Irritationen und Unverständnis aus.

Das Projekt der Sozial- und Kulturwissenschaft Ethnologie ist es, Lebensweisen, die zunächst als fremd oder anders erscheinen, zu erfassen und verstehbar zu machen. Ethnologische Forschung passiert immer nahe an den Menschen, “draußen auf der Straße”, wo Kultur und Gesellschaft stattfinden. Die Ethnologie versucht diesseits abstrakter Statistik Verständnis für tatsächliche Lebenswelten zu schaffen. Um dieses Ziel zu erreichen sind viele Wege möglich, wurden und werden gegangen.

“Cyberanthropology” bedeutet einen ethnologischen Ansatz, welcher die Beziehungen zwischen dem Menschen und komplexer Technologie ins Zentrum rückt, und als Ausgangspunkt benutzt.

Dabei spielen der Computer und das Internet natürlich eine wesentliche Rolle, aber die Kernidee der “Cyberanthropology” ist nicht darauf beschränkt.

“Cyberanthropology” wendet sich zwar auch an ein ethnologisches Fachpublikum, aber nicht nur. Zur Lektüre ist kein spezifisches Vorwissen notwendig und der Text ist allgemeinverständlich geschrieben. So wird im ersten Kapitel u.a. dargestellt, was die Wissenschaft Ethnologie eigentlich ist, was sie mit Technik und Technologie zu tun hat, und warum diese Verbindung gerade auch außerhalb des Elfenbeinturms relevant ist.

Die folgenden beiden Kapitel liefern wesentliche Hintergründe, die auch zeigen, warum das “Cyber-” in “Cyberanthropology” gerechtfertigt ist, und nicht einfach nur der Mode oder einem vermeintlichen Hype folgt. Im Kapitel “Kybernetik” wird das gleichnamige, in der unmittelbaren Nachkriegszeit gewachsene, wissenschaftliche Projekt vorgestellt, und an konkreten Beispielen gezeigt, wie sehr es Welt- und Menschenbild geprägt hat, und nach wie vor prägt. Dem folgt das darauf aufbauende Kapitel “Cyberpunk”. Den so bezeichneten globalen, inter- und transmedialen Diskurs, halte ich für die zentrale Quelle fiktionalen Materials, die es zu beachten und heranzuziehen gilt, wenn man zeitgenössische Lebenswelten, gegenwärtige Kultur verstehen möchte. Da das Kino nach wie vor das Medium mit der größten Reichweite ist, was die weltweite Vermittlung fiktionaler Inhalte anbelangt, liegt die Betonung dieses Kapitels auf dem Spielfilm – von Langs “Metropolis” und Chaplins “Modern Times” über Scotts “Alien” und “Blade Runner”, die “Matrix” Trilogie der Wachowski-Brüder, bis zu Camerons “Terminator” und “Avatar”.

Die Kapitel vier und fünf behandeln konkrete Beispiele, die meine Vision einer Cyberanthropology, und warum sie so, und nicht anders heißen soll, mit Fleisch versehen. Das Spektrum der Beispiele reicht von transnational zusammengesetzten Online-Gemeinschaften, die Computerspiele nicht nur spielen, sondern sie auseinandernehmen und neu zusammensetzen, über Inuit, die mit Hilfe einer Kombination aus GPS und ihren eigenen, traditionellen Navigationsmethoden den Weg durch Nacht und Eis am Polarkreis finden, bis hin zu Gangs, die mit ihren modifizierten Automobilen in Japans Metropolen illegale Rennen inszenieren, und darüber hinaus.

UPDATE: My publisher’s [you have no idea about how good it feels to be able to say ‘my publisher’—almost as good as saying ‘my tribe’] press division just notified me that a ↑first review [in German] has been published—more than short, but raving :-)

future/tech noir

Quite some water more on my mills which are grinding to construct what I like to call the cyberpunk discourse. The first installment of this construction you can read in my book ‘Cyberanthropology’ [in German], which will be published in August 2011 (and already ↑can be ordered in advance at amazon—did I already mention that?).

Very worthwhile are also the 2003 issues ↓23(2) Tech Noir and ↓23(4) Cyberpunk to the Singularity of the journal ↑Ylem: Artists Using Science and Technology.

moc quality

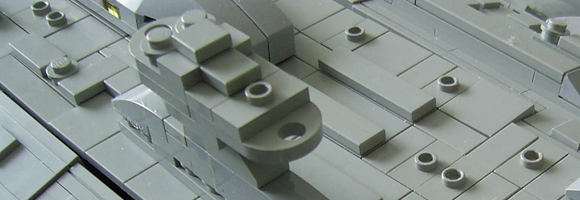

Just having hailed the professional standards of ↵artefacts stemming from the mod world, I now feel like presenting analogues from the ↵moc world. Just recently SAS voiced the opinion that, despite of their ingenuity and fabulous looks, mocs always are recognizable as mocs. Meaning, that they somehow lack a quality commercial Lego sets do feature. What this quality exactly constitutes remained elusive, even after further probing enquiry from my side. My opinion is that this may stand true for some mocs, but ain’t an absolute rule. Quite to the contrary. Here is the moc-version of the ↑TIE/In Interceptor, which first appeared in ‘↑Return of the Jedi‘ (Marquand 1983), ↑designed and built by IMPERIAL FLEET:

To my eye IMPERIAL FLEET’s version looks better than the Lego ↑set 6206, released in 2006 (on the left), and even better than the 2000 UCS (Ultimate Collector’s Series) ↑set 7181 (on the right). It may well be that I get carried away a bit now, but I think it looks even better than the models used in the movies ;-)

In principle IMPERIAL FLEET’s moc could be marketed as a set by TLG (The Lego Group)—it is at minifigure scale and although I don’t know the pieces-count, I assume that it still is sensible. This can not be said of the huge display-only models commissioned by TLG and created by its own inhouse Lego Master Builders. Like the famous ↵Venator by Erik Varszegi. Beasts like that, consisting of 35,000 Lego-pieces or more, clearly are beyond the resources of private individuals—so it seems. Allow me to teach you differently.

With all those dark-side imperial crafts, we for a change turn to the spaceships of the rebel alliance. In particular to the ‘Home One,’ like the Interceptor for the first time seen in ‘Return of the Jedi.’ ↑Wookieepedia knows:

Home One, also known as the Headquarters Frigate, was an MC80 Star Cruiser in the Alliance to Restore the Republic’s fleet, famous for its role at the Battle of Endor and as one of Admiral Ackbar’s flagships. It was the namesake of the Home One type subclass and was noted as being the largest and most advanced of the Rebel Star Cruisers.

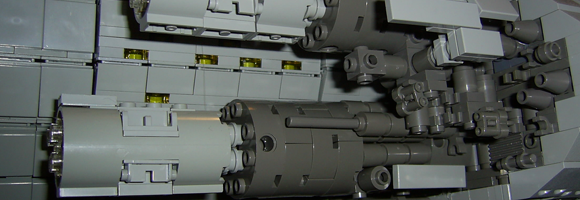

And here is what master moc-builder ↑Thomas Benedikt has to say on the ship:

For ages, well since episode VI came out, the rebel command ship was deemed by many, well, me, as the Impossible Ship. A ship with no right angles, no straight lines, just curves, bubbles, and obscure cylinders. Certainly such a ship could never be built out of Lego pieces and look good. But that day (conditional on the fact that people actually think it looks good) has arrived!

This hulk of a behemoth consists of 30,500 Lego-pieces and measures 208cm in length. The overall material cost was 5500,- US-$. Just to give you a visual idea of the scale of Thomas’ creation, ↑have some detail:

flowchart shaders

Biohazard’s modding tool, the ↑Source Shader Editor, is a ↑WYSIWYG editor, which ‘allows the user to create, compile and implement new ↑shaders easily into a source ↑mod without any preliminary knowledge of HLSL. The shaders are based on nodes which are connected over bridges to finally compose a flowgraph for each, the vertex and pixel shader […].’ It is a fine example of, and argument for the fact that modders not merely tweak games a bit, but sometimes create state-of-the-art tools sliding along the cutting edge of technology. I, and a lot of others, hope that this sooner or later will land Biohazard a job at Valve :-)

Years ago Grazer mentioned to me his fear that the death of modding was around the corner—due to the ever increasing complexity of game software, the members of the hobbyist scenes may no more be able to cope with. Well, the sociocultural practice of game modding hasn’t died until today. Quite to the contrary, it’s going strong. On the one hand Biohazard’s editor shows what technological heights modders can reach, demonstrating that they are able to cope with the complexity. On the other hand his tool unlocks potentials of the ↑Source ↑engine to other modders, who are not as deep down into it as he is.

For those who not at all are into this kind of technology: The video is worthwhile watching anyway, I think. its æsthetics and choreography tell quite a bit about how modders envision technology—plus, it has music from ↓the ‘Portal 2’ soundtrack (and maybe even a piece of cake).

moc styles

The cultural production of the ↵moc world features an amazing richness—in several dimensions. There is the vast range of scales to which the artefacts are made. But there also is a beautiful wealth of styles. Not to mention the incredible number of artefacts. And this although I for now almost exclusively have limited my scope to ‘Star Wars’ related mocs. But then again this was to be expected when dealing with aspects of the fandom of the biggest intellectual property franchise around.

Here are two examples. Both interpretations of the same subject, an imperial ↑AT-AT walker, are by Kevin ‘↑M<0><0>DSWIM‘ Ryhal and are showing, among other things and their sheer beauty, the radical transmediality of mocs. First the ↑steampunk version, which in its proportions is true to the original:

And this is M<0><0>DSWIM’s ↑chibi version of an AT-AT. ↑Wikipedia knows:

Chibi is a Japanese word meaning “short person” or “small child”. The word has gained currency amongst fans of manga and anime. Its meaning is of someone or some animal that is small. It can be translated as “little”, but is not used the same way as chiisana […] (tiny, small, little in Japanese) but rather cute. […] In English-speaking anime and manga fandom (otaku), the term chibi has mostly been conflated with the ‘↑super deformed‘ style of drawing characters with oversized heads or it can be used to describe child versions of characters.

omega legend

how the cyberpunk discourse infested the zombie genre

That may well be a truism, but ↑Stephen King is fond of zombie movies (1981: 134), of Romero’s classics of course in particular. Cyberpunk writers and fans are, too. But in ↑George A. Romero‘s debut ‘↑Night of the Living Dead‘ (1968) none of the canonical elements outlining cyberpunk as a genre can be found—with the exception of the postapocalyptic setting. Ten years later, during the historical threshold when the cyberpunk discourse reached critical mass and got manifest as a literary genre, the picture had changed. Richard Kadrey and Larry McCaffery sum it up:

‘↑Dawn of the Dead‘ (George Romero, 1978, Media). The mindless zombies who can eagerly (but placidly) rip-and-devour the flesh of guntoting bikers (when they’re not riding the escalators or being drawn to Blue Lite Specials) and prowl the shopping mall scene of this classic, horrifically funny film are, of course, the same folks we’ve hurried past on our way to the Cineplex 12. The nightmarish, punk extremities of surreal violence, the relentless exposure of capitalism’s banalizing effect on individuals, the insistence on visceral, bodily reality that our airbrushed, roboticized exteriors deny—all would find their way, in transmuted form, into cyberpunk’s own brand of dark humor, aesthetic extremity, and notions of guerilla-tactics survival. (Kadrey & McCaffery 1991: 23)

Literary critics may stab me for this, but those who like ↑Thomas Pynchon‘s writings also have to like Romero’s movies ;-)

But there is yet more to it, because a discursive link developed, and I found another mosaic-tile proofing that the cyberpunk-discourse through time gathers more and more momentum.

James Kakalios noted that the narrative snippets relating the mythical origins of superheroes get updated, at intervals are synchronized with the elements of the empirical world, with what happens in history and technoscience. In 1962 the spider which bit Peter Parker, gave him his superpowers and transformed him into Spider-Man, was affected by radioactivity. In the 2000s she was tinkered with by genetical engineering. (Kakalios 2005: 33) With the armoured knight it’s a similar story. In 1963 Tony Stark had his traumatic experiences, which led to him becoming Iron Man, in Vietnam. In the 2000s he lived through them in Afghanistan. It has to be like that, I guess—the adaptations allow the superhero-tales to fulfill their mythical functions.

What’s true for superheroes in a similar way is true for zombie movies. They keep pace with the world. Looked upon from my perspective: They more and more become subject to the cyberpunk discourse.

My argument will be most plausible, I hope, when I show this by the example of the remakes of one and the same subject matter.

It was ↑Mary Shelley who forcefully drove the idea of artificial life and the synthetic human being deep down into our cultural legacy. Her novel ‘↓Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus‘ (1818) accomplished this much more efficiently than the lore of the Golem could. So, cyberpunk owes her quite something. Lesser known is that she also gave us the topos of a world which is emptied by a pandemic of infectious disease until only one single human being is left: ‘↓The Last Man‘ (Shelley 1826).

We don’t know for sure, but it’s quite plausible that Richard Matheson was inspired by Shelley’s novel—or maybe even ↑its satirical movie interpretation (Blystone 1924)—when he wrote his own, ‘↑I am Legend‘ (Matheson 1954). In the novel the whole human race is turned into vampires. Although those vampires have to be killed by driving a stake through their hearts, and garlic is the repellant of choice, Matheson went considerably away from the supernatural vampire lore. In ‘I am legend’ the reason why humans turn into vampires is not to be found in the great beyond the grave, but under the microscope—it’s a germ. Both, George A. Romero and Stephen King, have praise for Matheson’s book and openly admit that it inspired them a lot.

Ten years after publication, Matheson’s novel for the first time is adapted to the silver screen as ‘↑The Last Man on Earth‘ (Ragona & Salkow 1964), starring the immortal and incomparable [Ladies and Gentlemen, please rise from your seats!] ↑Vincent Price. Matheson wrote parts of the screenplay (but was not satisfied with the final outcome), and the movie differs in some respects from the novel. The infected, for example, now very much live up [excuse the cheap pun] to the standard vision of a zombie as established by Romero’s movies. The novel’s vampires are fast and agile in contrast. As in the novel the reason for the zombification is a pandemic disease, the origin of which is not explained. Fittingly enough the movie’s main protagonist is a scientist, in the novel he was a plant worker.

In 1971 the next movie version of Matheson’s ‘I am legend’ came to the cinemas. ‘↑The Omega Man‘ (Sagal 1971) starring Charlton Heston—in the movie he pries quite some guns from dead cold hands. Meanwhile, in the form of New Wave Science Fiction, the cyberpunk discourse has reached significant mass and density. Most notable for our context here is ↑Harlan Ellison‘s ‘A Boy and His Dog’ (1969a, b), and ↑all which sprouted from it, which I won’t follow here and now. Instead back to ‘The Omega Man.’ The story’s backdrop has been changed, now the reason for the disease is man-made biological warfare and every trace of vampire lore is removed. Only the infected’s sensitivity to light remained. Although staying well within the Cold War scenario, the movie does not blame the USA, rather the biological war which killed almost all mankind was led between the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China (another connection to Ellison’s ‘A Boy and His Dog’).

For the 2007 movie version of ‘↑I am Legend‘ (Lawrence 2007), starring Will Smith, the Cold War background was no more interesting. Instead another core element of the cyberpunk discourse was placed at the heart of the story—the ambiguity of technology. Now the reason for the disease is a virus which originally was genetically engineered to fight cancer.

In the same year a B-picture variant was released: ‘↑I Am Omega‘ (Furst 2007), starring Mark Dacascos. Here also a genetically engineered virus has caused everything.

So much on the movies directly based upon Matheson’s novel. But there are more recent examples which successfully combine the zombie motif with cyberpunk aspects. ‘↑28 Days Later‘ (Boyle 2002), starring Cillian Murphy, its sequel ‘↑28 Weeks Later‘ (Fresnadillo 2007), and of course the ↑Resident Evil series (Anderson 2002, 2010; Witt 2004, Mulcahy 2007), starring Milla Jovovich. The Resident Evil franchise is especially interesting, because besides the genetically engineered virus we have an evil corporation and all kinds of cyberpunk æsthetics, from urban decay scenarios via the architecture of the Umbrella Corporation’s underground facilities, to Miss Jovovich’s costumes and choreography of movement. Which is little wonder, as the movies are based on the ↑computer game series of the same name. And computer games, especially the action- and first-person genre are even more subject to the cyberpunk discourse than movies ever were.

moc scales

Back in the 19th century, when you entered a museum where paintings of old masters were on exhibition, chances were that you encountered flocks of art students meticulously copying those pictures. During the heyday of academic painting this was a didactic standard procedure. Nowadays this practice more often than not is spat upon by the protagonists of the art scene.

Back in the heyday of Max-Payne modding countless recreations of characters, weapons, and architecture from the Matrix-franchise were accomplished by members of the community. Yours truly was ↑no exception.

Recreation of cherished artefacts from intellectual property franchises is a core practice within the according fandoms. I deem it to be appropriate to conceptualize said practice as an instance of appropriation. Successful recreation requires a lot of research and a lot of dealing with, and thinking about the original. And once you have recreated e.g. a spaceship from ‘Star Wars’ to your satisfaction, the relationship between you and the ship is altered for once and forever. When you see that spaceship again at the cinema or on your TV-screen, you will look upon it differently. Now there is a bond between you and the ship—in a way it’s your own now.

The Star-Wars aficionados within the ↵Lego-moc scene naturally are preoccupied a lot with recreating spacecrafts and everything else from Lucas’ galaxy far, far away. Creating and recreating by means of Lego-bricks and -pieces is a playful practice—I mean it in the sense of the definition of play by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman: ‘Play is free movement within a more rigid structure.’ (Salen & Zimmerman 2004: 304)

With Lego you can create almost everything, nevertheless the geometric and physical qualities of the pieces impose limits. There are rules which can’t be broken or bypassed, constituting the rigidness of the Lego-system. But then again Lego allows an astounding breadth of variation. For example in respect to the scale at which you intend to recreate an artefact by means of Lego.

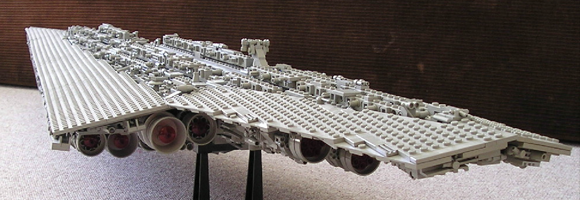

This is Erik Varszegi, a Lego Master Builder—meaning that he works as a model designer at the Lego company—leaning upon his famous recreation of a ↑Venator-class Star Destroyer as seen in e.g. ‘Revenge of the Sith’ (Lucas 2005). ↑Varszegi’s own creation consists of about 35,000 Lego-pieces, weighs 68kg, and is 2.44m long. The ‘original in the Star-Wars universe is 1,137m long, meaning that the Lego-model is at a scale of 1:466.

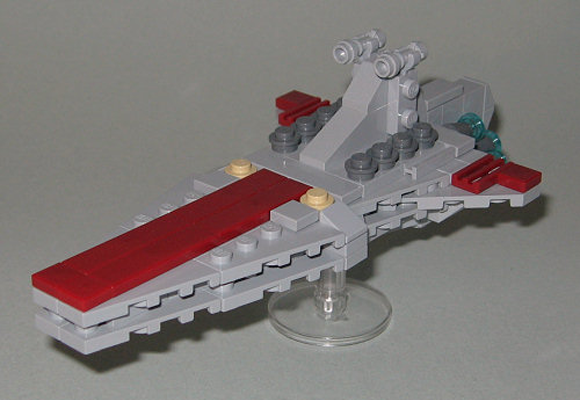

This ↑Venator by Polo aka ↑Atix_naid consists of 5340 pieces, is 112cm long, and therefore at a scale of 1:1015.

This is not a moc, but the official retail version of the Venator, Lego-set 8039, released in 2009. It consists of 1170 pieces, is 51cm long, and hence at a scale of 1:2229.

With this masterpiece by ↑Christopher ‘Legostein’ Deck we slowly approach the other extreme end of the moc-scales spectrum. This rendition consists of 220 pieces and is scale-matched to Lego-set 8099: Midi-Scale Imperial Star Destroyer. So it is at a scale of 1:6400.

But that’s not where Legostein stops:

His ↑Mini Venator Attack Cruiser consists of 120 pieces, at a scale of 1:7383.

And finally Legostein’s ↑Micro Venator Attack Cruiser consists of just 33 pieces, and is at a scale of 1:15902.

mocs and afols

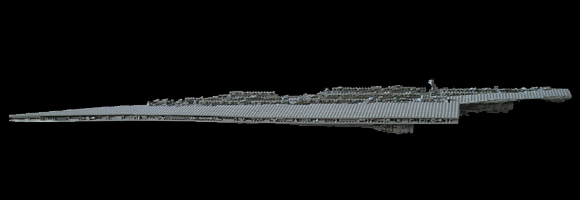

It may or may not be by accident, but ‘moc’ and ‘mod’ sound very similar. And indeed, both are close kin. The abbreviation ‘mod’ means ‘modification of a computer game,’ the playable addition to commercial computer-game software, produced by private individuals or groups of those. The acronym ‘moc’ in turn stands for ‘my own creation.’ Meant is an original three-dimensional design using Lego-bricks, quite often accomplished by an ‘afol’—an ‘adult fan of Lego’ … which is not a contradiction in terms, like ‘military intelligence’ is.*

The above pictured side elevation of the moc-version of the ‘Executor,’ the personal flagship of Lord Vader as first seen in ‘↑The Empire Strikes Back‘ (Kershner 1980), is a beautiful example. Created by Lasse Deleuran in 2003, ↑the final model is 157cm long and comprises 3461 Lego-parts:

Just for comparison: Later this year ↑Lego will publish an official set for building a Super Star Destroyer (Set 10221). The set comprises 3152 parts and the finished model will be about 125cm long.

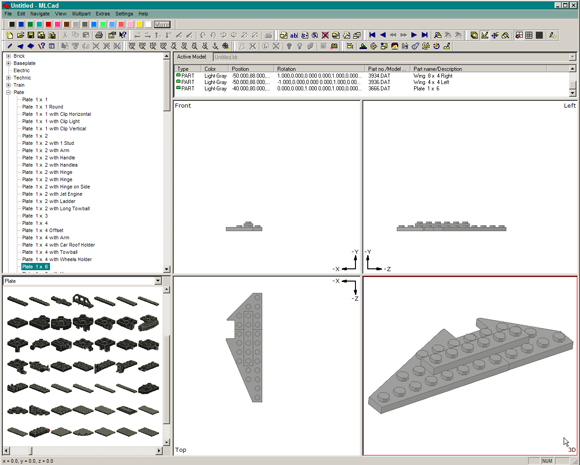

There is a gallery carrying a lot ↑more pictures of Deleuran’s ‘Executor’ at Brickshelf. If you strive to build it yourself, you can ↓download the complete instructions as .html plus the according MLCad file. Now, what is that? Well, it’s something which, like Deleuran’s ‘Executor,’ finely illustrates to what lengths the moccers go. It’s the 21st Century, and of course computer aided design (CAD) is put to use by the hardcore free Lego designers. There is an official tool, the ↑LEGO Digital Designer (LDD), downloadable from the Lego Group’s websites, and then there are the high-end tools from the free software scene like the ↑LDraw-based Windows editor ↑Mike’s LEGO CAD (MLCad) by Michael Lachmann:

MLCad (Mike’s Lego CAD) is a powerful CAD system specifically designed to create building instructions as known from Lego, for your own Lego models and creations. MLCad reads and writes LDraw (a program of James Jessiman) compatible files but in an extensive window based environment. The program helps to create building instructions, which show step by step how to build a model.

It looks and feels like professional 3D-visualization or CAD applications, with different viewports and all … it is professional software (↑LDraw installation, ↑MLCad tutorial). Here is how it looks:

The screenshot shows the first step of my own rendition of a ↑TIE Interceptor:

There are sub-disciplines within the moc-scene, like creating in minifigure-scale, or in micro-scale—as small as possible, but still looking gorgeous. Scalewise my little piece is somewhere in-between, but with it I may have founded a new sub-discipline: all parts used are pre-1990 ;-)

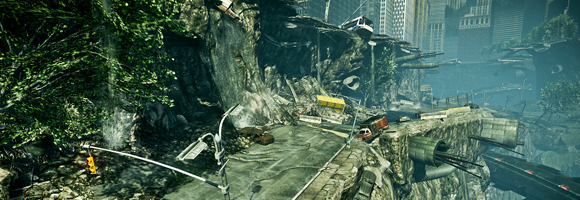

postapocalyptic interviews

At level-design.org there is an interesting ↑interview with Hélder Pinto aka [HP], my old friend from the Max-Payne modding-scene who became a level artist at Crytek. The above is an example of his art, the devastated Madison Square as it appears in Crysis 2. If it wouldn’t be such an old cliché, I’d say you truly are a master of desaster, my man. Speaking of which, eurogamer.org carries a recent ↑interview with John Carmack, the master of Doom. Engine John not only talks about id’s upcoming title Rage, but also on technology at large, e.g. about the end of Moore’s law, the apocalypse of game consoles, and such—more than worthwhile. And, yes, both games are decidedly cyberpunkish. Here’s the Dead City from Rage: